Midnight at the Blackbird Cafe

by Heather Webber

An enchanting tale about grief, forgiveness, and healing, Anna Kate and Natalie are the protagonists. After her grandmother, Zee, dies, Anna Kate journeys to the rural town of Wicklow, Alabama, where her mom grew up. Zee, owner of the Blackbird Cafe, left Anna Kate her cafe in her will to keep or sell, stipulating Anna Kate must live in Wicklow for two months before she can legally inherit it. Natalie grew up in Wicklow. She’s a young widow with a sweet one-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Ollie. She struggles with depression over the loss of Matt, her husband, but is determined to gain independence from her parents and be a good and loving mom to Ollie.

Full of magical realism, bewitched blackbirds sing at midnight and homemade blackberry pies create mysterious dreams. I thoroughly enjoyed this delightful, immersing novel.

Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town

by Barbara Demick

Tibet is frequently referred to as “the roof of the world.” It conjures up visions of Buddhist monks chanting and spiritual people living harmoniously in a peaceful, bucolic paradise. This is an illusion.

The book’s title is based on despicable events caused by Mao Zedong’s Communist troops in 1935 when they attacked the local people and desecrated their monasteries in the small town of Ngaba. The soldiers stole religious items, defecated on religious texts, and ate the holy figurines that had been sculpted out of barley, flour, and butter made by the monks—they were literally “eating the Buddha.” Beginning in the 1950’s with the 10-year-long Cultural Revolution, China began its campaign of ethnic cleansing and tearing down monasteries in an attempt to eradicate Tibet’s religion and culture, and populate Tibet with ethnic Han Chinese people. In the Communist manner, Tibetan homes, farms, livestock, and businesses were seized and given to Chinese immigrants.

The Chinese Han population now greatly outnumbers the indigenous Tibetan population. Through assimilation and the homogenization of Tibetan culture into the Han population, Tibetan culture will eventually be erased.

Since the invasion 70 years ago, 6,000 monasteries have been destroyed by the Chinese. In her eye-opening book, the author describes the changes that occurred up to present day from Tibetans’ personal accounts whom she met and interviewed. She provides an important and necessary voice to the Tibetan people. The average Westerner is probably completely unaware of what is happening today in Tibet.

In 1966, with the beginning of the violent Cultural Revolution—in which Gonpo, the last Tibetan royal princess, initially participated in—slogans such as “Beat to a pulp any and all persons who go against Mao Zedong thought” and “Wage war against the old society” abounded.

“The objective was to overthrow people in authority and to transform culture not in line with socialist thought and economy.”

Upper class people and academics were either imprisoned or banished to do hard labor in hash, remote areas of China. Gonpo and her parents, the Tibetan King and Queen, were ostracized from society. Gonpo was sent to a rural area of China to perform forced labor. Her parents were murdered. Her accounts, along with other Tibetans, provide heartbreaking stories that continue to present day. The majority of the Tibetans would be willing to cooperate with China if they were offered similar rights the Hun Chinese who relocate to Tibet receive, such as the right for their children to learn their own language, and to worship their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who the Chinese continually denounces.

“The level of fear among Tibetans is comparable to what I’ve seen in North Korea,” states Demick. “The government’s control already is so complete their surveillance of online communications so thorough, the closed-circuit cameras so ubiquitous, the biometric tracking of the population so communications so thorough, the closed-circuit cameras so ubiquitous, the biometric tracking of the population so advanced, that they maintain order almost seamlessly.”

“Uighurs have it even worse than Tibetans: as of this writing, up to one million Uighurs are being held against their will in “patriotic education” camps where they do menial work for little or no pay and undergo Communist Party indoctrination. “

Demick was bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times in Beijing and Seoul, and previously reported from the Middle East and Balkans for the Philadelphia Inquirer. She graduated from Yale College. Her work has won many awards including the Samuel Johnson prize (now the Baillie Gifford prize) for non-fiction in the U.K., the Overseas Press Club’s human rights reporting award, the Polk Award, the Robert F. Kennedy award, and Stanford University’s Shorenstein Award for Asia coverage.

King Of The Confessors

by Thomas Hoving

“The book is about a young, opportunistic, ambitious nobody-assistant-curator of the Cloisters in 1963, which I was, wading through the underbelly of the art world to acquire a great prize.”

~ Thomas Hoving

I originally read this intriguing book years ago. After recently re-reading it, I found it just as entertaining and immersing. A true story, it reads like a detective novel. According to Hoving, in the early ’60s as a young assistant curator at the Cloisters Museum of the Metropolitan Art Museum in New York City, he heard of a magnificent carved cross thought to be fake. This is the fascinating account of how Hoving became obsessed with it, researched its history, and ultimately purchased it for the Museum, after three years of frustrating negotiations.

When Hoving first saw the cross, black grime was still embedded on it. He thought it probably had been in a grave or buried in the earth somewhere in Europe for centuries. The cross is carved walrus ivory, and topped by the inscription “King of the Confessors.” Now in the collection of the Cloisters Museum of the Metropolitan Art Museum, the acclaimed English Romanesque cross, which dates to the mid-12th century, is considered a masterpiece of medieval sculpture. Both sides of the extraordinary cross are covered with carved figures nearly ½-inch in size, so intricate and detailed, the nails in the hands of the Christ figure can be seen. The scenes depict events from the Old and New Testaments. There are approximately a hundred inscriptions written in medieval Latin. It’s known as The Cloisters Cross at the museum and is one of its most notable pieces. (The Cloisters Museum is a branch of the Metropolitan Museum, but physically a separate building and museum. It specializes in European medieval art and architecture).

Hoving, however, refers to it as the Bury St. Edmunds Cross. After reading the book, readers will discover the reason, its astounding background, who possibly created it, and the controversies surrounding the cross. In addition to Hoving’s gripping descriptions about his attempts to buy the cross from Topic Ante Mimara, a secretive and mysterious character, he also provides an extremely witty and illuminating account of how he eventually became the Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hoving was only 36 when he was appointed director of the Met—very young for such an illustrious position. Innovative and daring, he brought fresh ideas to the Met. He said “The museum needs reform. Sprucing up. Dynamics. Electricity. The place is moribund. Gray. It’s dying. The morale of the staff is low. The energy seems to have vanished…The Met seems to me like a great ocean liner, engines off, wallowing in a dead calm, moving only because of the swell.”

Hoving told the trustees that the museum “needed to be made popular, to communicate the grandeur of the fifty centuries of art the Met possessed.” His critics called him arrogant and egotistical. I call him brilliant, ingenious, and a genuine bon vivant. Never before had there been “blockbuster shows” at any museum. He created the first “blockbuster”: the King Tut exhibit, “Treasures of Tutankhamun,” which traveled to six cities in the U.S. from 1976 to 1979. Millions of people lined up to see it. It created the era of “blockbuster” museum exhibits. I was fortunate to see it in Los Angeles. Other notable “blockbusters” followed.

The fabulous Egyptian Temple of Dendor currently housed in the museum and a Frank Lloyd Wright house were both acquired personally by him, along with other spectacular art. Some innovative ideas of his included locating a museum shop and dining options within the museum. He also authored some terrific books, including his memoir, “Making the Mummies Dance.”

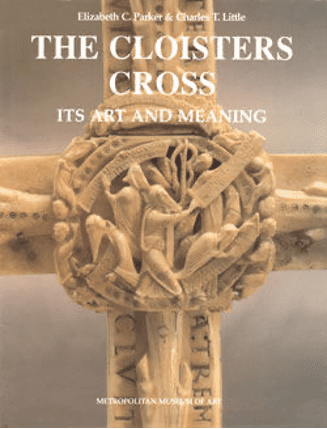

The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning

by Elizabeth Peters & Charles T. Little

After reading Hoving’s absolutely arresting account regarding the cross, I went to the Cloisters in New York to see it and was thrilled at its magnificence and breathtaking carving. I purchased the marvelous now out-of-print book about it, “The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning,” published by the Metropolitan Museum. I’ve recently donated it to PCL, where its detailed history and beautiful illustrations are now available to read and see. A free e-book is also available online.